3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Image by Ebenezer | 22 July 2010

Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

With the Civil War raging — the most fearsome and brutal of conflicts — entomologists, lepidopterists, and naturalists nevertheless found ways to practice their craft and for some to engage in their passion. The battlefields were far enough away for butterfly enthusiasts to go into the field and collect specimens, then debate the finer points of entomology in their publications or at their confabs.

One discussion in the 1863 edition of Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Philadelphia focused on the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (genus Papilio) pictured here. Was the yellow and black version — species glaucus — a male and only a male? If true, was the female Eastern Tiger Swallowtail not yellow, but black or dark blue? Perhaps two visually different butterflies, like many songbirds, are expressions of sexual variations of the same species. If so, the yellow male for sure is brighter and more showy than the female — much like Cardinal birds. Who knows?

Mr. Jacob Stauffer of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, offered his opinion, writing: “The query is:— if, as some suppose, the P. glaucus and turnus are merely sexual varieties, then it follows that the larvæ differ as essentially as do the perfect insects, both in color and habit, leaving a doubt as to the fact of the two being but male and female of the same species.” I've read this passage a dozen times and still can't make sense of it. But I soldier on.

Let's Clear This Thing Up

A Mr. Ridings in a section entitled “Verbal Communications” sought to clear up the confusion. The editor stated “that he (Mr. Ridings) was quite satisfied that Papilio glaucus is only a black female of P. turnus. He had taken a black female in connection with a yellow male as long ago as 1832, and since that time he has taken females of all shades from a deep black to a dark yellow, but never observed or heard of a female being as light colored as a male, neither a male as dark colored as a female.” So, there you have it.

Naturally, there was no immediate resolution, though eventually … over time … a long time … the issue was resolved … maybe … because the species name turnus is now a synonym for the standard designation glaucus. Well, sorta kinda in a way. If you've read this deep into the narrative, then you are likely as confused as I am. Not that it matters much. But I do like today's image of the bright yellow and black Eastern Tiger Swallowtail — a male — dining on the flower of the lantana on 22 July 2010 … a long time ago. As for the war, much longer ago. The Blues won.

Rabbits, Hummingbirds

and The Resurrection

Midnight Draws Nigh

By Ebenezer Baldwin Bowles

30 July 2020

The Tale of El Rey

Midsummer arrived on a hot wind from the south, bringing not rain but a dry heat. Then came the welcome rain, a splash yesterday and a hard and fleeting stream today with lighter showers tonight. And the thunder! It rumbles and roils through the highlands.

The grasses, shrubs, trees … all the vegetable world is rejoicing. The rain has come. The primal thirst is slaked.

Midnight draws nigh, Anthony Payne's “A Day in the Life of a Mayfly” plays on the stereo, and I peck away at another attempt to communicate with you and the world OUT THERE. It's scary sometimes, this Universe, but keeping my voice alive is necessary to prevent “going gray” in spirit and in thought … before the words begin to crumble, before I can't make sense of any of them.

For reasons I cannot comprehend, the passage of the seasons, one after another, no longer inspires me like it once did. Ninety degrees, thirty degrees, the sweet seventy in the middle — it seems so mundane and old hat. I can't say I've lost my curiosity. Not yet, but I fear I shall — the loss — the cynicism — all too soon.

“I'll pray for you,” our sweet friend the Benedictine nun tells me.

3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Buds of the Resurrection Lily | Image by Ebenezer | 25 July 2019

The Resurrection Arrives

The most pleasing event this July is the ritual emergence of the Resurrection Lilies, rising-up from the warm soil on two-foot tall stalks to reveal striking pink and yellow flowers. Most folks call them “Naked Ladies,” but that's a vulgar name for such a majestic flower. Not that I shy away from the vulgar — I've been known to curse up a storm — but I'd rather seek out the refined voice and find it where I may. Lord willin' and the creeks don't rise, I'll tell you the story of the Resurrection Lily next week when the time comes.

The female rabbit who lives here at 3 Dog Acres brought three baby bunnies to dine at the bird banquet tables. The Mistress of the Hacienda, my sweet Freddie Liz, enjoys watching them play on the pebbled ground of El Rey while mother rabbit stands guard. Then one day last week only two bunnies showed up. We found the scant remains of the third bunny in the Dog Yard, though I doubt the hounds killed her. The hawks are hunting now. I buried the little one in the Back Forty.

The Guise of an Explorer

Having roamed the Earth since 1949, I've passed into old age without the burden of excessive grumbling. I can be difficult, I am told — more than once — but I'm working on developing a better attitude. Healing drugs and healing therapy literally change my Universe. Even at this late hour, I'm a work in progress.

With neither money nor power nor sex as motivation, I arrive at the byted page in the guise of an explorer of the natural realm — with the means of production at my fingertips and my voice and eye attuned to the moment. I continue to believe I have something of value to share, all the while realizing that what has been will be again, what has been done will be done again, and that there is nothing new under the Sun.

3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Tropical Hibiscus | Image by Ebenezer | 24 September 2016

The Birds Dine at El Rey

To admit from the comfort and isolation of the Cottage that I miss the face-to-face fellowship of pre-Covid reality — well, I'll admit it: I miss you. Every one of you. Right now.

In the morning and most late afternoons we feed the birds: the cardinals, the indigo buntings, the blue jays, the doves, the chickadees, the wrens, the sparrows, the woodpeckers, the robins, the brown-headed cowbirds, and the yellow canaries. Others, too, I suppose — these are the birds we recognize, but all are welcome at the table.

We don’t employ bird feeders to minister to the hungry flock. Instead, we sprinkle a mix of milo seed, white millet seed, cracked corn, nyjer seed of the African yellow daisy, wheat seed, and black oil sunflower seed onto the bird banquet tables. Through the east facing picture window of the study we watch (and admire) the hungry critters flit and prance, dart and dance as they dine on the delicacies.

The tables are nine hefty limestone rocks with mostly flat tops, standing from eighteen to twenty-four inches tall and arranged in a rim, running about thirty feet from north-to-south with an arbor entrance in the center. My friend Roy Baird helped me design and construct the project. Truth be told, Roy, his master mason assistant, and one powerful forklift did all the heavy lifting. With luck on our side, each stone fit nicely beside the other, as planned, including the four-ton rock we call Grandfather.

3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

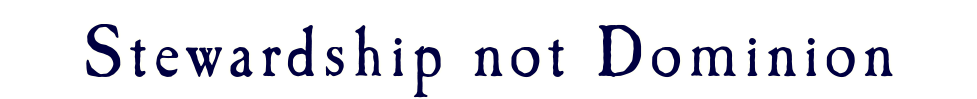

Black and Blue Sage | Image by Ebenezer | 25 July 2017

Watching the Hummingbirds

The rim of rocks forms a front-door patio we call El Rey, named after our favorite lodge in the whole wide world, El Rey Court in Santa Fe. An expansive Golden Raintree, a Kwanzan Cherry, a mature Forsythia and two Redbuds provide the luscious bower over Patio El Rey.

The only birds who visit but do not dine at El Rey are the crows and one mated pair of hummingbirds, who come closer and closer to we humans as the air grows warmer. As they've done for many a year, the pair arrive in late spring and stay until the first cold snap of autumn. The experts say the hummingbirds don't mate for life, that they live three to five years, but I refuse to believe them.

With time, the tiny hummingbirds grow comfortable with our presence and fly just a few feet in front of our eyes. They pause in mid-air, greet us, then race away into the tall branches of the oaks or the tulip poplar, where they land on a thin twig to rest for a moment before dipping into the flowers of the Sage, the Lantana, the Petunia, the Trumpet Vine, and the Mimosa.

They’re not shy but brave, these lovely flying creatures — and they’ve claimed our yard as their exclusive hunting and feeding ground. Territorial to a fault, they killed an interloper two years ago. The battle was fierce and primal. On the hard, dry Earth of summer, I found the intruder … slain in combat. We remember.

3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

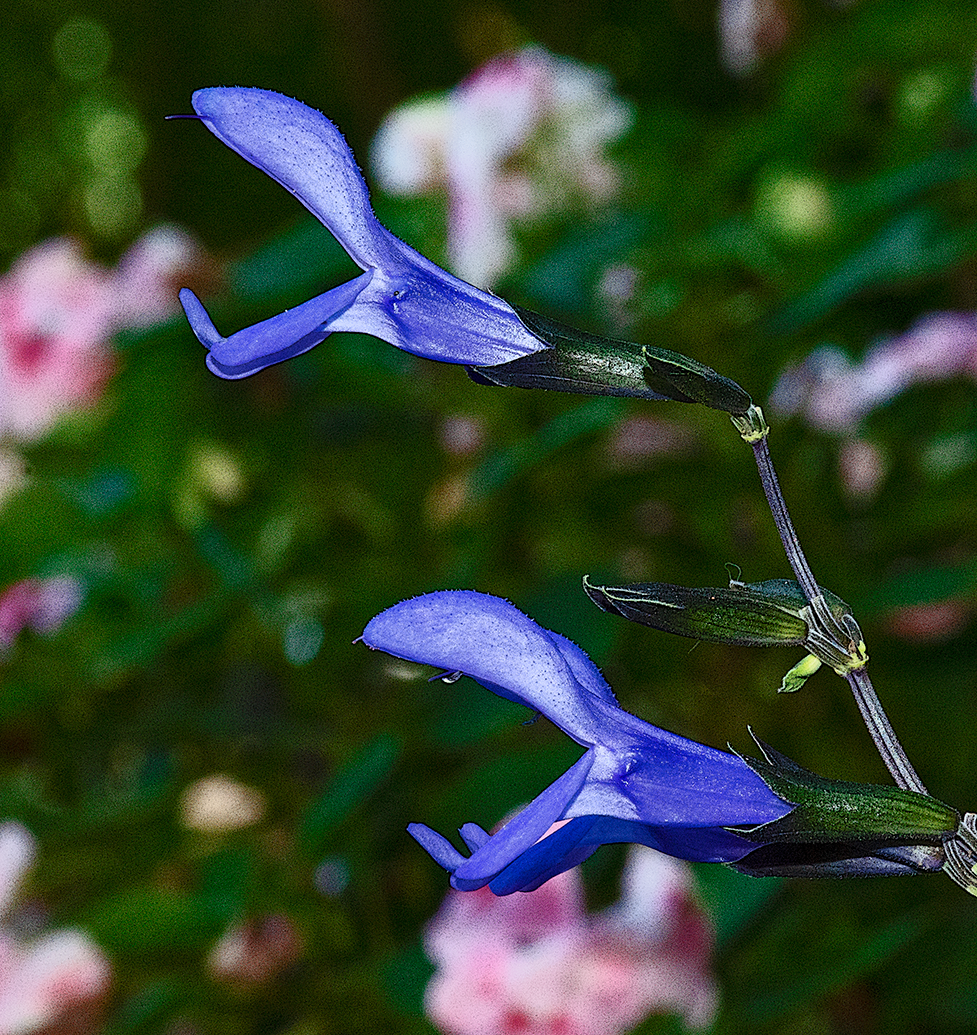

Image by Ebenezer | 12 August 2019

Tulip-Tree Beauty

In my elder years, death doesn't come easy. Nor should it, I suppose, but I'm loathe to slay any living creature — not even aggressive red wasps or mean looking spiders crawling about the house. I'm grateful for the digital camera because I can collect wildflowers and insects in electric pixels, not in boxes with specimens pierced by pins.

That might explain why I was dismayed to read Celia Thaxter's report of her encounter with a creature she called “the most marvelous moth in the world.” What did that distinction earn the moth? “It was so happy and beautiful flying about so confidingly in the bright sunshine within reach of my hand!” she wrote in An Island Garden (1894). “But I knew of someone to whom it would be a treasure, so I threw a light veil over, caught it, and sent it softly to sleep forever with some chloroform. It was Ællopos Titan, very rare, and found in the tropics.”

The creature shown above is the Tulip-Tree Beauty (Epimecis hortaria), a dramatic looking moth collected by camera a few moments after midnight of a warm eve in midsummer 2019. The moth collected by Celia Thaxter in the 1890s was the Titan Sphinx, a wide-bodied, plain looking brown critter. Beauty for sure is in the eye of the beholder.

Those red eyes of our midnight Beauty are likely a trick of artificial light, or else an undecipherable signal from the far side of the Sun. She was fearless, our Tulip-Tree Beauty, striking a pose on the storm door window before flying away into the darkness.

Voice. Come out of the silence.

Say Something.

Appear in the form of a spider

Or a moth beating the curtain.

— Theodore Roethke

A Beetle's Eye View

and Sled Dogs from Long Ago

Have you heard about the tiny camera researchers have strapped to a beetle's back? We've seen the pictures and they're pretty awesome. The system weighs less than a dollar bill and includes a maneuverable camera arm controlled by a smartphone. The system streams monochrome video with a resolution of 160x120 pixels and is powered by a 10-milliamp battery lasting up to six hours.

Do you experience pain? Rhetorical question … of course you do. A study published in Current Biology blames our distant ancestors the Neanderthals. DNA tests on three Neanderthal skeletons found mutations in gene SCN9A, which controls how pain signals are delivered to the brain. The presence of this mutation, researchers contend, lowers the threshold for feeling pain.

Hot and getting hotter? How about one of the coldest settlements on Planet Earth recording an all-time high temperature? That's the case at Longyearbyen, located at the Norway Arctic Archipelago Svalbard, where on 23 July the archipelago recorded a high of 21.7 degrees (71.06 Fahrenheit). “The hotter temperature would thaw the frozen ground, causing structures like buildings, roads, and airports to collapse,” Nature World News reports. High temperatures would also increase the incidences of landslides and avalanche.”

Traveling to the remote Siberian island of Zhokhov, looking deep into the past, we discover archaelogical evidence that humans bred sled dogs about 9,500 years ago. A study published in Science on 25 June tells about DNA evidence “suggesting the dogs had already begun to evolve to adapt to the temperatures and oxygen requirements of the job … making it the first evidence for any sort of dog breeding in the archaeological record.” Good dogs! Biscuit time.

3 Dog Acres | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Image by Ebenezer | 10 April 2014

Ohio Buckeye

A tree with a rich heritage and several million admirers (at least), the Ohio Buckeye (Aesculus glabra) in 1840 “became a fixed sobriquet of the State of Ohio and its people, known and understood wherever either is spoken of, and likely to continue as long as either shall be remembered or the English language endures,” William M. Farrar opined in the 1847 publication Historical Collections of Ohio. That's a strong statement and a bold prediction … some alarmists among us might predict that the tree will outlive the language. I doubt any of us will be around when the verdict is announced. And, by way of aside, I'll save you a moment or two: That clunky word means nickname or pseudonym. We had to look it up. And by way of another aside, the author of the sweet little essay quoted here served with the Sherman Brigade, United States Army, during the Civil War.

“In those early days, when a boundless and lofty wilderness overshadowed every habitation, to destroy the trees and make way for the growth of corn was the great object — hic labor, hic opus erat. Now, the lands where the Buckeye abounded were, from the special softness of its wood, the easiest of all others to ‘clear,’ and in this way it afforded valuable though negative assistance to the first settlers,” Mr. Farrar wrote.

Good Friends with the Sugar Maple

In an interesting friendship, anywhere the Buckeye grew in the Ohio River valley, so grew the sugar maple — “for it was not only the best wood of the forest for troughs, but everywhere grew side by side with the graceful and delicious sugar maple.”

The Buckeye is also a tree with superpowers of a sort. “In all our woods there is not a tree so hard to kill as the Buckeye,” Mr. Farrar wrote. “The deepest ‘girdling’ does not ‘deaden it,’ and even after it is cut down and worked up into the side of a cabin, it will send out young branches, denoting to all the world that Buckeyes are not easily conquered, and could with difficulty be destroyed.” Perhaps by kryptonite.

A Good Luck Buck Nut

As for the origin of its sobriquet (there's that word again), the Buckeye “derives its name from the resemblance of its nut to the eye of the buck, the finest organ of our noblest wild animal,” Mr. Farrar wrote. BTW, the Ohio Buckeye is aka the American Horse Chestnut.

We planted the Buckeye now growing outside the south-facing windows of the Cottage six or seven years ago. Last year it produced its first and only Buckeye nuts — by the squirrel's count five, maybe six nuts total. We plucked the last nut from the tree and handed it to our pal Dave Leisure, who was rambling through the gardens with us. Dave put the Buckeye nut into his pocket. A potent good luck charm, the Buckeye is an equal to the horseshoe, the rabbit's foot, or a four-leaf clover. Trust us: Dave is enjoying an exceptionally good year.

Polar Bears Under Threat

As Ice Continues to Melt

Polar bears need ice, but what happens when the ice melts? The bears (Ursus maritimus) are forced onto land, and not able to capture seals, and thus not able to obtain sufficient nutrition to survive the winter. That's one too many not-ables for comfort. Under the headline “Global Warming Is Driving Polar Bears Toward Extinction, Researchers Say,” The New York Times reports that a just released study concludes that polar bears may be extinct by the end of the century. “There is very little chance that polar bears would persist anywhere in the world, except perhaps in the very high Arctic in one small subpopulation” if greenhouse-gas emissions continue at so-called business-as-usual levels, said Peter K. Molnar, a researcher at the University of Toronto Scarborough and lead author of the study, which was published Monday (27 July) in the journal Nature Climate Change. The estimated polar bear population in the arctic is twenty-five thousand.

Bambi Land | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Flower of the Mimosa tree | Image by Ebenezer | 18 July 2020

Peaches and Plums

In the shade beneath the Mimosa tree,

down in the grass, where nobody sees,

are the tiniest ladybugs living their lives

and the smallest of bumblebees building their hives.

The butterflies fly, and the hummingbirds hum,

around two little boys eating peaches and plums.

—Kelly Grettler—

Underneath the Mimosa Tree 2020

A Special Kind of Magic

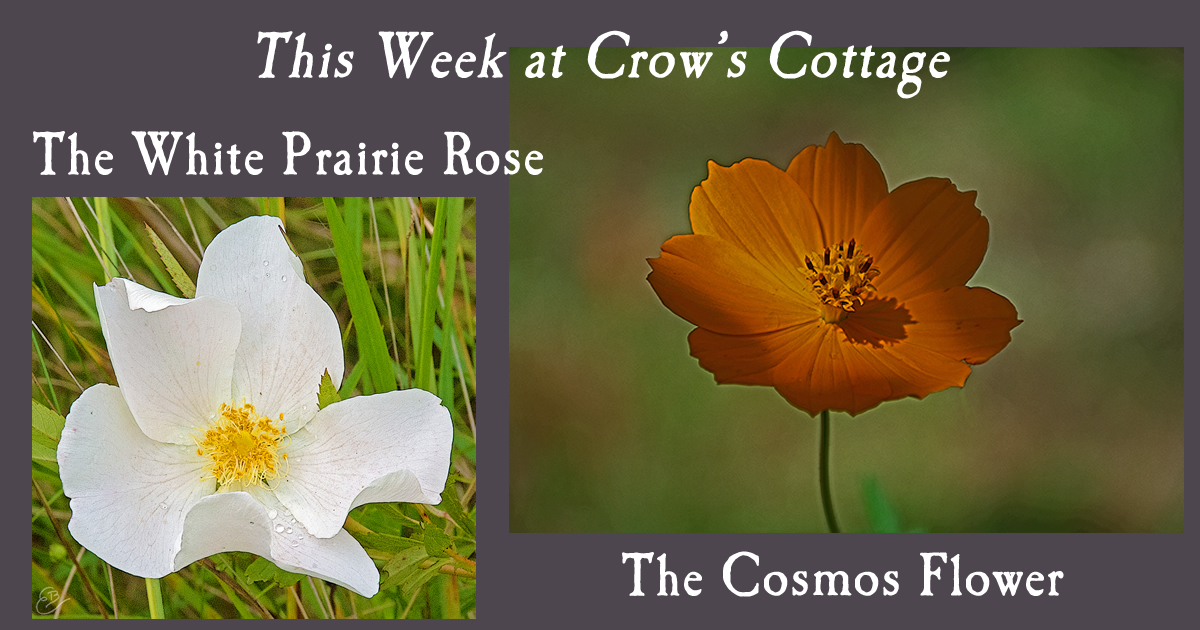

Some trees possess a right-nice flavor of magic for children … and for adults, too, but only those who shake off cynicism and oblige their childlike imagination. The Mimosa is one of those special trees … and some of you out there abide amongst a special tribe of adults — resident dreamers, rare visionaries, and artists at life — who've learned how to see through a child's eyes.

“Set here and there in this country will be a Mimosa tree, with its smell in the rain like a cool melon cut, its puffs of pale flowers settled in its sensitive leaves,” Eudora Welty wrote in Some Notes on River Country (2003). One of those “puffs of pale flowers” aka pom-poms aka bottle brushes is pictured above.

Look closely at the flowers of this enchanting tree and you'll see hundreds of long, showy stamens with yellow tips to entice pollinators. The flowers come in pairs and seem to float on the Spirit of the Winds. When we checked this afternoon, a dozen or so black swallowtails and a lone tiger swallowtail were drinking the sweet Mimosa nectar.

Bambi Land | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Leaf of a Mimosa tree | Image by Ebenezer | 18 July 2020

The Professor Calls Her the Silktree

If one doesn't like the name Mimosa, then don't fret. There's another choice: Silktree. The late Dr. Dwight Munson Moore, who wrote the book about Arkansas trees, preferred Silktree. No disrespect whatsoever to the professor, but here at the Cottage we're sticking with Mimosa (Albizia julibrissin Durazz).

“To the south of the old house was a large circular grass plot, almost surrounded by a high Osage Orange hedge,” Caroline Couper Lovell writes in The Light of Other Days (1995). “In its centre was an old Mimosa tree covered with ivy, which we called The Ivy Tree, and in this we girls simply lived, each of us having a special ‘room’ of our own. It was a delicious abode, for the Mimosa blooms on the ends of the outstretched limbs were like rosy powder-puffs, filling the air with a delicate nectarine fragrance, and the sound of hummingbirds and bees.”

Playwright Romila Thapar of New Delhi was much more succinct in the play Sakuntala. The heroine and mythical Hindu figure Sakuntala fell under the sway of the magic tree, crying out: “The new branches on this Mimosa tree are like fingers moving in the wind, calling to me. I must go to it!”

Freddie Liz, the Mistress of the Hacienda, also fell under sway of the magical Mimosa. A voracious reader and an adventurous teen, she liked to crawl up into a fork of one of several Mimosas growing at her home. “It was perfect,” she told me. “I could lay back in my favorite nook and read to my heart's content. I spent hours hiding up in the tree, reading and daydreaming — and it smelled good, too. Just a cool, beautiful place to escape and read.”

To her dismay, Freddie Liz watched as, one by one, her Mimosa reading room fell to an insidious disease, most likely Fusarium wilt. Other Mimosas grew in her yard, and all perished. Identified in 1935 by scientists in Tyron, North Carolina, the Fusarium wilt disease raged throughout the South, eradicating thousands of Mimosas, and literally wiping out the tree from cities across the land.

Bambi Land | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Trunks of a very big Mimosa tree | Image by Ebenezer | 27 July 2020

A Heavenly Dream

A gladsome sight it is to see,

In blossom the Mimosa tree.

Like golden moonlight doth it seem,

The moonlight of a heavenly dream;

A sunset lustre, chased and cold,

A pearly splendour, blent with gold;

That in its loveliness profound,

The waters have a mellower sound.

—Richard Howitt—

1868

It's almost as if the Mimosa puts a spell on visitors. True enough, she is an inviting tree, easy to climb and soft on the skin. “Above me, Marco and Sera are climbing high into the branches of the Mimosa tree, showering me in yellow flowers,” Antonello Preto wrote in The Mimosa Tree (2013). “I look up. Surely, if there were a god somewhere in my house, he would be hanging out up there, in the fluffy golden branches of our Mimosa tree in full bloom.”

The Mimosa under our stewardship resides at Bambi Land, the two-acre mini prairie across the lane from the Cottage — and she's in full, majestic bloom as I sit here tonight. The yellow that Mr. Preto sees must come from the tips of the stamens, but when I spy our Mimosa's flowers from a distance, I see a delicate swirl of purple and white.

Our friend Madame Blavatsky understood the arcane nature of the Mimosa. “Several of the Mimosæ alternately open and close their petals as the full moon emerges from or is obscured by clouds,” she wrote in her masterwork, Isis Unveiled. Madame Blavatsky asked, “Does The Moon Influence Vegetation?” The action of the Mimosa was cited in her study, which concluded with an answer. Yes.

Bambi Land | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Mimosa flower | Image by Ebenezer | 27 July 2020

We Had No Idea

We came here at the cherry slab to explore the Mimosa tree, but not to this extent. It just came upon us. A naturalist's work oft takes on a life of its own … in directions not foreseen, but almost alway' rewarding. Until we opened the books in search of knowledge, we had no idea the Mimosa has so deeply moved poets, playmates, and prophets.

Some amongst us will argue that the Mimosa isn't native, but so what. Does that fact make her less worthy? That she came to North America from Persia, or China, or Australia isn't the point. She's here now and here to stay, having been naturalized for two and a half centuries. Our Mimosa is an Arkansas Mimosa, growing tall and proud.

Helen Give Up? Never!

Let's end our study with a passage from Helen Keller's The Story of My Life. Brave beyond measure, the blind and deaf overcomer decided one day to climb a tree, which she did — only to be assaulted by a fierce wind, which left Helen afraid of tree climbing. But Helen give up? Never.

“It was the sweet allurement of the Mimosa tree in full bloom that finally overcame my fears,” Helen writes. “One beautiful spring morning when I was alone in the summer-house, reading, I became aware of a wonderful subtle fragrance in the air. I started up and instinctively stretched out my hands. It seemed as if the spirit of spring had passed through the summer house. ‘What is it?’ I asked, and the next minute I recognized the aroma of the Mimosa blossoms. I felt my way to the end of the garden, knowing that the Mimosa tree was near the fence, at the turn of the path. Yes, there it was, all quivering in the warm sunshine, its blossom-laden branches almost touching the long grass. Was there ever anything so exquisitely beautiful in the world before! Its delicate blossoms shrank from the slightest earthly touch; it seemed as if a tree of paradise had been transplanted to earth.”

Ever brave, Helen Keller climbed that tree. “I sat there for a long, long time, feeling like a fairy on a rosy cloud. After that I spent many happy hours in my tree of paradise, thinking fair thoughts and dreaming bright dreams.”

Bambi Land | rural Washington County, Arkansas

Seed pods of the Mimosa | Image by Ebenezer | 31 August 2017

As always, we invite you to write us letter of encouragement or correction. You can even chastise us if you're respectful. Expect a courteous and timely reply. And let us know if you'd like to receive a notice about new features. Our address is ebenezer@crowscottage.com