|

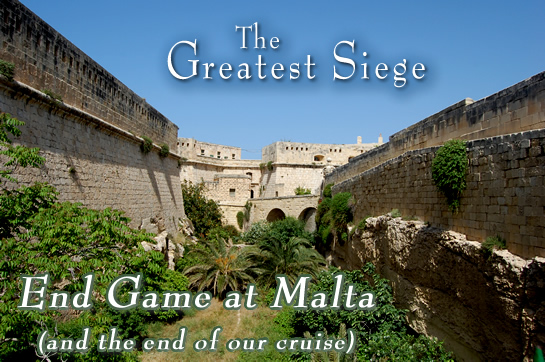

The Moat at Fort St. Elmo

Photographs by Ron Fritze

Digital post production by Joe Dempsey

Suleiman Takes It on the Chin.

By Ron Fritze

DATELINE: At sea after departing Malta

Filed on May 21, 2009

Posted on Planet Clio on July 14, 2009

If the Turks should prevail against the Isle of Malta,

it is uncertain what further peril might follow

to the rest of Christendom.

— Queen Elizabeth I.

The morning after leaving Alexandria, we enjoyed our usual breakfast in the Windjammer. Later in the morning we played some Trivia at the Windjammer and did pretty well (but did not win). At 2 that afternoon I gave my lecture on the siege of Malta to about 50 people. It appeared to be well-received.

An Old Soldier, but Not a Bore.

Afterward, one older Englishman came up and started talking. I believe he must have been stationed at Malta for a period of time. Based on his accent and dress, I would presume he was an officer. He was quite knowledgeable about the fortifications and artillery on the island. He kept apologizing about being a bore on the subject, but I assured him that I found it quite interesting, which I did.

Another older English couple who had been faithful attendees of my lectures came up to talk. They are great travelers and told stories about all sorts of places. The husband had developed angina, so they have to stick with relatively well-provided cruises these days, but it sounds like they’d had some real adventures. We later met them in the Windjammer for the afternoon snack time and had a wonderful hour of conversation.

A little later, while I was imbibing in the Schooner Bar, an Internet hotspot on the ship, an American from my lecture group, David Brown from Pennsylvania, stopped to talk. He said he was reading Ernle Bradford’s Great Siege: Malta 1565, a book I had recommended during my lecture. Back in Pennsylvania, David works for the highway department, which explains his commentary about all the trash along the Egyptian highway between Alexandria and Cairo, and how sorry it was. As I mentioned in my previous cruise report, the trashy scene in Egypt caught everyone’s eye. We would hear comments similar to David’s for the rest of the cruise.

Filthy, Pestering, Expensive....

But Worth It!

On another occasion we spoke with an Englishman named Jeff, who is a pretty big guy, about his time in Egypt. He told us that his party had tried to go on their own, but when they left the cruise terminal, they immediately encountered extremely filthy conditions. They were also pestered by people trying to sell them stuff. After an hour, they gave up and went back to the ship.

Two days later we had a similar conversation with a similarly large Australian man. For some reason, neither the English nor the Australian group went to the pyramids — and they had not been there previously either. Going to the pyramids is a bit expensive at $175 per person, but if you are going to go that far, you might as well spend a little more and have the experience of your life.

Of course, you can do what the English and the Australian guys did and go it on your own in Alexandria. You’ll have a different kind of experience, and it’s free of charge — assuming that you make it back without being robbed or killed. Take my advice, go to the pyramids.

The Happy, Friendly Hard Life

Egypt is no country for old men. In fact, it is no country for the 101st Airborne. Don’t get me wrong, my fundamental observation is that the Egyptians are generally a happy and friendly people. That is in itself a tribute to their fortitude and stoicism, given the hard life that most of them live. But there are more than a few Egyptians who are pests, members of a subculture of the extremely poor. Theirs is not a society where hard work and perseverance will get one ahead in life.

What Egypt does do for me, however, is increase my sympathy for those thousands of American and British soldiers who have been given all-expense-paid trips to Iraq and Afghanistan. Conditions are worse there — and some of the natives are distinctly hostile in the extreme.

Entrance of Grand Harbor of Malta. Fort St. Elmo is on the right and La Valletta and Mount Sciberras are in the center.

A Travel Lesson and a Bow's-Eye View

We arrived at Malta on 20 May. The ship did not dock until shortly before two. We had to be back on board by six.

Approaching Malta at noon gave all sorts of opportunities for taking pictures. Twylia and I got out on the bow of the ship. We were at about six stories up, which is the lowest down you can get on the ship and still get a bow’s-eye view of the approach. Malta came into sight and then slowly but surely got bigger and bigger. The pilot tug came out to guide the ship into the harbor, which has a relatively narrow entrance into the Grand Harbor. I got all sorts of good shots of Fort St. Elmo, Fort St. Angelo, and La Valletta. I also got sunburned. In my photographer’s enthusiasm I forgot to bring both my hat and the sunscreen. But my first sunburn of the cruise wasn’t all that bad. I chalked it up to another travel lesson learned — and at least I wasn’t burned lobster red like many of my fellow passengers fresh off the Egyptian broiler.

Malta is a very historic island. St. Paul visited Malta on his way to Rome. It was not a voluntary stopover. He was traveling on as a prisoner when a storm wrecked the ship. Maltese are Christians, despite their proximity to North Africa and a past period of Muslim occupation. In fact, they claim to have been converted to Christianity by St. Paul. If you want to read the narrative, check out The Book of Acts, Chapters 27 and 28.

Malta’s

Malta’s

strategic location has brought the island its fair share of fighting and sieges. During World War II, the German and Italian air forces tried to bomb Malta into oblivion, or at least some form of submission, but the island held out. An even greater siege occurred in 1565 — and that prolonged event was the subject of my cruise lecture.

Gozo, Milka, Bozo, and Credibility.

Malta is the largest island in a small archipelago located less than 60 miles (90 km) south of Sicily and some 200 miles (290 km) east of Tunisia. It is about 18 miles (27 km) in length and 9 miles (14 km) in width with an area of 95 square miles (246 sq. km.) There are two smaller islands to the north, Gozo and Comino, as well as several very small and rocky uninhabited islands. I told Twylia that Gozo was originally named Milka but the name had been changed. I added that it was the birthplace of Bozo as well. She did not believe any of that stuff as my credibility is shot. As you can see, the poor woman suffers a lot.

Phoenician traders who settled Malta called it Maleth, meaning “haven.” The Greeks corrupted the name to Melita, meaning “honey,” from which the name Malta is derived.

In 1565, Malta was the headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller, who used it as a base for piratical raids against Muslim shipping. Who were the Knights Hospitaller besides being the lords of Malta? Over time they went by a number of names, including the Order of the

Hospital and the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. In 1310 they conquered Rhodes, an event which led to a new name, the Knights of Rhodes. By the time the 1530s rolled around, they were commonly called the Knights of Malta.

Hospital and the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. In 1310 they conquered Rhodes, an event which led to a new name, the Knights of Rhodes. By the time the 1530s rolled around, they were commonly called the Knights of Malta.

This famous military-religious order originated shortly after the First Crusade's conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 and provided accommodations to pilgrims along with general almsgiving and medical care. By about 1123 the Hospitallers began to provide military protection for pilgrims. Along with the other Crusaders they were expelled from the Holy Land when the Mameluke Turks of Egypt captured Acre in 1291. That led to the Knights moving to Rhodes.

The Powerful Ottoman Turks

Viewed the Hospitallers at a Threat.

Meanwhile, a new power had arisen in Asia Minor (present day Turkey). The new power was the Ottoman Turks, who transformed themselves into a formidable and well-nigh irresistible military force. By 1453 the Ottomans had besieged and captured Constantinople, the last remnant of the Roman Empire, and made it their capital. They were not finished, either. Conquests continued in the Balkan Peninsula, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and North Africa. They also viewed the Hospitallers on Rhodes as a threat and inconvenience — and finally drove them out in 1522.

Rendered homeless for seven years, the Hospitallers received the island of Malta as a grant from the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1530 — hence the tribute of a gold falcon that serves as the plot focus of the classic film The Maltese Falcon. From that base they defended Christian shipping in the Mediterranean from the Ottoman navy and Barbary corsairs and conducted even more raids on Moslem vessels.

To the Islamic world, the Hospitallers’ piracy was intolerable, forcing the Ottoman Sultan, the leader of the Islamic world, to honor his duty and dispatch forces to stop the Christian pirates. That sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566), was a seventy-year-old man, but he still wanted to expand his empire. He had the power to attack and capture Malta, so in October 1564 he decided to launch an expedition against Malta the following spring.

Although Malta was a barren island and ruled by the Knights, it was peopled by a native population of very ancient Christians, whose conversion, they claimed, extended all the way back to St. Paul. Speaking a dialect related to Arabic, they numbered about 12,000 on Malta, with another 5,000 on Gozo and Comino.

LaValette Springs into Action.

The principle town was Mdina, but the Knights chose to settle beside the grand harbor in the village of Birgu. There the Knights proceeded to strengthen the village fortifications massively, building walls to protect Birgu from land attack and strengthening the fort of St. Angelo at the end of the peninsula, which commanded the entrance to

the grand harbor. Senglea, a village on the other side of the harbor, was protected by the fort of St. Michael. The Knights also built a new fort called St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula to provide the Grand Harbor with additional protection and also prevent enemies from using the Marsamucetto harbor.

the grand harbor. Senglea, a village on the other side of the harbor, was protected by the fort of St. Michael. The Knights also built a new fort called St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula to provide the Grand Harbor with additional protection and also prevent enemies from using the Marsamucetto harbor.

Despite the strength of their fortifications, the Knights’ position suffered from being surrounded by high ground, which would allow a besieging force to shoot their cannon down into the towns. Anticipating an Ottoman attack, Jean Parisot de LaValette, the Grand Master of the Hospitallers (1494-1568), gathered supplies of food and ammunition to withstand a long siege. He also called for help from the Hospitallers not in residence at Malta and the Christian rulers of Europe.

In the spring of 1565, LaValette’s military force of 8,000 to 9,000 included 700 Knights among the army of Maltese irregulars and other troops from Sicily. The old and infirm of Malta were evacuated to Sicily to get them out of harms way and reduce the number of mouths that needed to be feed during the siege.

The Ottoman Turkish force was co-commanded the Admiral Piali, a Hungarian foundling who had been taken into the Sultan’s household and risen to the highest maritime rank. The land forces were under the command of Mustapha Pasha, a Turk. The two commanders were to be advised by the famous and highly skilled Dragut, a corsair admiral based in North Africa and in service to the Ottomans. The Ottoman fleet consisted of nearly 200 ships, mostly galleys. It carried over 30,000 troops, which does not count the galley slaves or the sailors on the ships. Of those troops, 6,300 were part of the elite Janissary Corps of musketeers. These were slave soldiers who lived a Spartan-like existence.

The massive armada sailed from the Bosporus of Constantinople on 29 March 1565. During the course of the siege, the Ottoman army would be joined by at least 10,000 additional troops from Egypt and the other Islamic lands of North Africa.

Fort St. Elmo

Taking a Stand at St. Elmo

Meanwhile LaValette garrisoned isolated St. Elmo with 52 Knights and 800 additional troops which included 200 Spanish soldiers from Sicily. His judgment was that St. Elmo was crucial to keeping the Turks out of the harbor of the Marsamucetto as long as possible. On 18 May the watch at St. Elmo sighted the arrival of the Ottoman fleet. The alarm was sounded and all the inhabitants of Malta took refuge in the fortified towns. Most Maltese went to Mdina.

LaValette also ordered his troops to poison all the wells outside his fortified positions. While this did not render the water completely undrinkable, it contributed to the outbreak of dysentery in the Turkish camp as the siege progressed. LaValette’s strategy was to take advantage of his fortified positions and not confront the enemy in the field. It was a sound strategy, given how much he was outnumbered. His biggest problem was the high ground around Birgu, Senglea, and St. Elmo.

The Ottomans began landing at the southern bay of Marsasirocco on 19 May, confident they would easily conquer Malta in less than two weeks. Moving on Birgu, they assaulted its walls on 21 May which resulted in the death of 21 defenders and several hundred Turks. This initial encounter did reveal that the Turkish musket fire was more accurate than that of the Europeans due to the better weapons of the Turks. Admiral Piali demanded that the first objective be St. Elmo so that he could have use of the safer Marsamuscetto harbor. Mustapha Pasha did not agree. He wanted to capture Mdina and focus on Birgu, but he went along with Piali, who argued that the safety of the fleet was paramount.

The Turkish fleet under command of Admiral Piali

Drag the Cannons to High Ground.

Dragging cannons up to Mount Sciberras, the Ottomans began bombarding St. Elmo on 24 May. They expected that it would fall within a week. LaValette considered St. Elmo the key to Malta’s defense. Throughout the Turkish assaults, he continually reinforced St. Elmo by sending soldiers across the harbor in boats. The decision not to capture Mdina was a big mistake on the part of the Ottoman commanders as LaValette had stationed all his cavalry there. This mobile force continually harassed the Turks from the rear, a tactic that would eventually prove very fruitful for the defenders.

To attack St. Elmo, the Turkish troops had to cross a moat under fire. The defenders had raised drawbridges and broken down other bridges so the Turks had to construct portable bridges. Such massed attacks were costly in terms of casualties, but the Ottoman commanders had little regard for the lives of their men, given the common belief that if a Muslim died in battle with the infidels, they would go straight to a very fleshy paradise. Furious attacks continued through 29 May with tremendous casualties among the Turks, although LaValette had to continually reinforce the garrison at St. Elmo with fresh troops.

Dragut arrived shortly after 29 May. He regarded the focus on St. Elmo to be a mistake, but he also thought that since they were committed, the Ottomans could not abandon the attack and would have to continue until St. Elmo fell. Known by the title of “The Drawn Sword of Islam” and trained as an artillery man by the Mamelukes of Egypt, Dragut brought increased order to the Turkish bombardment. He added batteries at Dragut Point and Gallows Point to bring fire on St. Elmo from all directions. Soon the Turks were firing about 7,000 rounds into St. Elmo every day. The fort was slowly being pulverized.

With summer at hand, the temperatures began to climb, providing an unexpected and ominous ally for the defenders. The hot sun and warm air ripened the unburied dead and bred disease, while the poisoned water gave rise to dysentery in the Turkish camp.

The Ottoman attacks on St. Elmo continued with fierce assaults spearheaded by Janissaries on 3 June and 7 June. The defenders, however, wreaked havoc among the Turkish attackers. Despite their success, some of the younger Knights in St. Elmo demanded on 8 June that the fort be evacuated. Instead, they were shamed into staying the course.

An intense night assault on 10 June killed 60 defenders, but also resulted in 1,500 deaths among the Janissaries. The cannons of St. Angelo were used to support the defenders of St. Elmo with enfilading fire.

Stunning and Decisive Blows.

Vicious fighting continued. On 18 June the Ottomans suffered the stunning and decisive blows. The first came when Dragut was mortally wounded by shrapnel from a cannonball. Only his thick turban prevented instant death, but the head wound put him out of action and eventually killed him a week later. The second blow came when artillery fire from the defenders killed the Aga of the Janissaries. A day later the Master General of the Turkish ordnance was killed; he was the second in command of the army to Mustapha Pasha.

Vicious fighting continued. On 18 June the Ottomans suffered the stunning and decisive blows. The first came when Dragut was mortally wounded by shrapnel from a cannonball. Only his thick turban prevented instant death, but the head wound put him out of action and eventually killed him a week later. The second blow came when artillery fire from the defenders killed the Aga of the Janissaries. A day later the Master General of the Turkish ordnance was killed; he was the second in command of the army to Mustapha Pasha.

Another furious assault on 22 June resulted in 2,000 more Turkish casualties, but the war of attrition was beginning to decisively favor the attackers. It was clear that St. Elmo was doomed. Turkish troops breached the walls, and on 23 June a Turkish assault overran the fort. Nine Knights were captured by Dragut’s men, never to be seen again and probably dying as galley slaves. Five Maltese swam to safety, but the rest of the garrison perished.

In the course of the month-long siege of St. Elmo, the Turks lost 8,000 men killed, roughly a quarter of their troops, including many elite Janissaries. About 1,500 defenders had died. As Mustapha Pasha looked from the ruins of captured St. Elmo across the Grand Harbor to the fort of St. Angelo, he asked: “Allah! If so small a son has cost us so dear, what price shall we have to pay for so large a father?”

Although the fall of St. Elmo was a great blow to the defenders of Malta, on the same day they received an important boost. Another 42 knights along with a force of soldiers from Sicily totaling 700 men landed on Malta and managed to sneak past the Turkish lines to reinforce Birgu by crossing Kalkara Creek. Meanwhile, hoping to avoid more bloodshed, Mustapha Pasha offered the Knights honorable terms of surrender. LaValette refused and so Mustapha began setting up his cannon to bombard Birgu and Senglea. His plan was to attack the fort of St. Michael at Senglea first.

To increase the pressure on the Knights, Mustapha had 80 ships drug across the peninsula of Mount Sciberras to threaten the defenders while bypassing the guns of St. Angelo. But a Greek noble, Lascaris, deserted the Turkish army and informed LaValette of the Turkish plan to attack across the water. To counter this plan, the Knights erected a palisade in the water with the intent of preventing the Turks from landing.

The Cavalry Ride to the Rescue.

After several weeks of preparation and bombardment, Mustapha ordered the first major attack on Senglea. Result: 3,000 Turkish dead and 250 defenders dead. The palisades had successfully blocked the landing of the Turkish boats. Due to the high casualties, Mustapha returned to the tactic of continual bombardment of Birgu and Senglea. After an all-out bombardment on 2 August, the Turks attempted to storm both St. Michael and the Birgu wall at the same time, but were repulsed with heavy casualties. On 7 August Mustapha ordered a simultaneous attack on St. Michael and Birgu to prevent the garrisons from reinforcing each other. Despite terrible casualties, the Ottoman forces were on the verge of capturing St. Michael when retreat was called. The Maltese cavalry in Mdina had launched a raid on the Turkish camp, massacring the sick and the wounded, plundering what they could, and destroying the rest. It was a demoralizing blow to the already demoralized Ottoman army.

Ottoman forces began to dig tunnels under the walls of Birgu with a plan to fill them with gunpowder and blow up or undermine the fortifications of the Knights. On 18 August, a mine under the Castille bastion of Birgu was ignited, causing part of the wall to collapse. At that point the Ottomans launched coordinated attacks on Senglea and Birgu. Piali lead the assault on the damaged Birgu wall and penetrated into the town, but LaValette lead the counter-attack to recaptured the breach and save the day.

The Turks also erected siege towers to threaten the walls of Birgu. LaValette’s nephew was killed attempted to destroy the great Turkish siege tower on 19 August. Although the tower survived that day, the Knights destroyed it soon after. It collapsed in a wrecked heap. The next day, 20 August, the Knights even managed to capture another Turkish tower.

Both sides were becoming desperate. The Ottomans were running low on gunpowder, a deficit evident to the defenders of Malta, who saw the rate of fire from the Turkish cannons slacken significantly. Inside Birgu, the Grand Council of the Knights urged LaValette to abandon Birgu and retreat to St. Angelo. He refused as it would mean total defeat soon after. Meanwhile Mustapha ordered the capture of Mdina, but that effort was abandoned in the face of strong resistance.

From the beginning of the siege, LaValette and the Knights had been expecting a large relief force from Sicily. The Spanish Viceroy of Sicily, Don Garcia de Toledo, had promised to send an army by the end of June, but it failed to appear. He promised again for July, but it also never sailed. Finally on 25 August, the Spanish fleet with 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers sailed from Syracuse on Sicily for Malta. A storm, however, delayed and damaged it. The fleet returned to Sicily and did not sail again until 4 September.

The Turks attempted one more mass assault on 1 September. It, too, failed. Disease, an enemy even more potent than the guns of the defenders of Malta, ravaged the Turkish camp. The fighting force of Mustapha and Piali had fallen into terrible condition, with their remaining troop strength reduced to around 15,000 men.

The Spanish force from Sicily arrived on 7 September and began landing at Mellieha Bay on the north coast of Malta. The reinforcements totaled about 8,000 men, meaning the defenders were still outnumbered. The wily LaValette sent double agents into the Turkish camp to inform Mustapha that 16,000 Spanish troops had landed. Mustapha ordered an evacuation, which proceeded on 8 September. But when Turkish scout ships informed Mustapha of the small size of the relief fleet, he ordered his troops to disembark and return to the battle. Piali disagreed with the order, a common occurrence between the two men.

The split between leaders reduced the attacking Turkish force to 9,000 troops, who were sent against the 8,000 men of the relief force. The Turks were turned back and forced to retreat to their ships. It was not a rout, however, and the Turks managed to sail back to Constantinople.

In the War of Attrition,

The Christian Knights Prevail.

The Great Siege was done, having lasted four extremely costly months. Seven thousand Christian soldiers and Maltese died defending the island, including 250 of the Knights Hospitallers. Although the garrison consisted of 9,000 men at the beginning of battle, only 600 remained capable of bearing arms at its end. The Ottoman army lost at least 30,000 men. Of the 31,000 men who left Constantinople in March, only 10,000 returned. The remaining losses were inflicted on the allied troops from Egypt and North Africa. Suleiman the Magnificent had suffered only the second significant defeat during in his long reign, the first having occurred at the siege of Vienna in 1529. The defeat at Malta halted the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Suleiman died the next year while campaigning in Hungary.

The Great Siege was done, having lasted four extremely costly months. Seven thousand Christian soldiers and Maltese died defending the island, including 250 of the Knights Hospitallers. Although the garrison consisted of 9,000 men at the beginning of battle, only 600 remained capable of bearing arms at its end. The Ottoman army lost at least 30,000 men. Of the 31,000 men who left Constantinople in March, only 10,000 returned. The remaining losses were inflicted on the allied troops from Egypt and North Africa. Suleiman the Magnificent had suffered only the second significant defeat during in his long reign, the first having occurred at the siege of Vienna in 1529. The defeat at Malta halted the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Suleiman died the next year while campaigning in Hungary.

After the siege was over, Birgu was renamed Vittoriosa or “Victorious City.” Senglea was renamed Invitta or “The Unconquered.” LaValette moved the home of the Knights to Mount Sciberras in 1566. The new town on the Mount was named Humillina Civitas Valettae [the most humble city of Valetta] in honor of the Grand Master. LaValette suffered a stroke while hunting in July 1568. He lingered for several weeks, dying on 21 August, and was buried in the Cathedral of St. John, which became the resting place of all the Grand Masters who followed.

Malta is a very pleasant place these days. Unfortunately, the cruise schedule allowed for only a few hours off ship. Twylia and I walked into La Valletta, which meant a steep trek up Mount Sciberras. It gave us a pretty good idea of what the Turks had to endure when they dragged their cannons up the mountain.

As you can see from some of the pictures, things are surprisingly close together. The walk from the cruise terminal to the walls of St. Elmo is probably about two-thirds of a mile. We got a good idea of the lay of the land by walking down Republic Street, which took us past the Cathedral of St. John and the Palace of the Grand Masters, now the Maltese Parliament building.

You can walk to the gates of Fort St. Elmo, but you can’t go inside because it now serves as home to the Maltese police academy.

Thwarted, we walked up Republic Street. A short way up the street, we came across a little hole in the wall café and stopped for something cool to drink. I took the opportunity to try the local Maltese beer, which is named Cisk, a lager. Yes, Cisk is tasty, but it’s bitter in comparison to Mythos. I definitely prefer my Mythos.

Thwarted, we walked up Republic Street. A short way up the street, we came across a little hole in the wall café and stopped for something cool to drink. I took the opportunity to try the local Maltese beer, which is named Cisk, a lager. Yes, Cisk is tasty, but it’s bitter in comparison to Mythos. I definitely prefer my Mythos.

Reflecting on my beer, a sobering thought came to mind. We were relaxing in a former killing field where once, in early June of 1565, thousands of Turkish soldiers had perished in assaults on St. Elmo.

Finishing off the drinks, we headed back up Mount Sciberras for a little souvenir shopping. I even managed to find a place that sold Walker’s crisps from England, my favorite. Then it was back to the ship. At the cruise terminal we saw a jewelry store that was selling its own version of the cat pin Twylia has been coveting since our visit to Santorini two years ago. The pin on Santorini was nicer, or at least we think it was, but it may be that the Santorini cat has grown in our memories.

Worth another Look.

Both of us agree that we would gladly to return to Malta if the opportunity arose. I would certainly like to explore more of the island. It is pleasant and clean — and my observation is that Maltese girls are quite pretty. But if you tell Twylia I said that, I will deny it vehemently.

Kalkara Creek with Fort St. Angelo and Birgu to the left

Leaving the harbor, we got some more nice pictures, including a few good ones of the pilot’s boat. With that we left the isle of the great siege. The next day was a sea day. My team won the morning trivia contest — and I put us over the top by correctly answering a five-pointer. The question: “What year did the Turks capture Constantinople?” “1453,” I said. Our group won these nice little backpacks for daytrips. Maybe a backpack would have prevented the pickpocket from lifting my wallet at the beginning of the trip. Oh well. May the Greek pickpocket be condemned to live in a Cairo slum.

We bid our farewells to Jeff and his wife Judy, and handed out tips to our waiters, Radu from Romania and Ali from Turkey, both quite good. The next day endured a long but uneventful trip back to Athens, Alabama, which took 24 hours.

It was a good cruise. Not our best. Truthfully, it was my least favorite. We saw some wonderful things and I’m very glad we went. But getting my pocket-picked was a downer. And both of us are still melancholy from the death of Otto. This cruise was not a great one for meeting people, although things were picking up at the end. I think it was partly a function the cruise having the highest proportion of non-English speaking people of any we have sailed on. As a result, we frequently ended up at a table in the Windjammer with folks we couldn’t converse with. How I love a good conversation!

The heat wave in Egypt was also a disappointment, especially since we had scheduled a May cruise to avoid that problem. Instead, we ran into an unseasonable heat wave. And the beer survey was stunted on this trip, although I did discover I could get Stella Artois on draft at the Schooner bar.

Would I do it again? Of course. But give me a week to rest up and get a new wallet and driver’s license.

Let me conclude with a digression on Malta. A conversation between Catherine de Medici, the Queen of France and Antoine de la Roche, a Knight Commander of the Hospitallers summed up the siege this way....

Catherine de Medici:

Was it really the greatest siege? Greater even than Rhodes?

Antoine de la Roche, Knight Commander of the Hospitallers:

Yes, Madame, greater even than Rhodes. It was the greatest siege in history.

Let the

Cruise

Begin

|

Of Palermo,

Pickpockets,

a Porthole,

the Parthenon |

The Colossus,

Pyramids,

and the

Sphinx

|

Cannes,

Florence,

Rome,

and Sardinia |

Of Mountains,

Monkeys,

and Men

|

Rambling

'tween

the Itchen and

the Scratchen |

Click on the black panther to read about Ron Fritze's new book,

Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science, and Pseudo-religions. |

Malta’s

Malta’s Hospital and the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. In 1310 they conquered Rhodes, an event which led to a new name, the Knights of Rhodes. By the time the 1530s rolled around, they were commonly called the Knights of Malta.

Hospital and the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. In 1310 they conquered Rhodes, an event which led to a new name, the Knights of Rhodes. By the time the 1530s rolled around, they were commonly called the Knights of Malta. the grand harbor. Senglea, a village on the other side of the harbor, was protected by the fort of St. Michael. The Knights also built a new fort called St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula to provide the Grand Harbor with additional protection and also prevent enemies from using the Marsamucetto harbor.

the grand harbor. Senglea, a village on the other side of the harbor, was protected by the fort of St. Michael. The Knights also built a new fort called St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula to provide the Grand Harbor with additional protection and also prevent enemies from using the Marsamucetto harbor.

Vicious fighting continued. On 18 June the Ottomans suffered the stunning and decisive blows. The first came when Dragut was mortally wounded by shrapnel from a cannonball. Only his thick turban prevented instant death, but the head wound put him out of action and eventually killed him a week later. The second blow came when artillery fire from the defenders killed the Aga of the Janissaries. A day later the Master General of the Turkish ordnance was killed; he was the second in command of the army to Mustapha Pasha.

Vicious fighting continued. On 18 June the Ottomans suffered the stunning and decisive blows. The first came when Dragut was mortally wounded by shrapnel from a cannonball. Only his thick turban prevented instant death, but the head wound put him out of action and eventually killed him a week later. The second blow came when artillery fire from the defenders killed the Aga of the Janissaries. A day later the Master General of the Turkish ordnance was killed; he was the second in command of the army to Mustapha Pasha. The Great Siege was done, having lasted four extremely costly months. Seven thousand Christian soldiers and Maltese died defending the island, including 250 of the Knights Hospitallers. Although the garrison consisted of 9,000 men at the beginning of battle, only 600 remained capable of bearing arms at its end. The Ottoman army lost at least 30,000 men. Of the 31,000 men who left Constantinople in March, only 10,000 returned. The remaining losses were inflicted on the allied troops from Egypt and North Africa. Suleiman the Magnificent had suffered only the second significant defeat during in his long reign, the first having occurred at the siege of Vienna in 1529. The defeat at Malta halted the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Suleiman died the next year while campaigning in Hungary.

The Great Siege was done, having lasted four extremely costly months. Seven thousand Christian soldiers and Maltese died defending the island, including 250 of the Knights Hospitallers. Although the garrison consisted of 9,000 men at the beginning of battle, only 600 remained capable of bearing arms at its end. The Ottoman army lost at least 30,000 men. Of the 31,000 men who left Constantinople in March, only 10,000 returned. The remaining losses were inflicted on the allied troops from Egypt and North Africa. Suleiman the Magnificent had suffered only the second significant defeat during in his long reign, the first having occurred at the siege of Vienna in 1529. The defeat at Malta halted the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Suleiman died the next year while campaigning in Hungary.

Thwarted, we walked up Republic Street. A short way up the street, we came across a little hole in the wall café and stopped for something cool to drink. I took the opportunity to try the local Maltese beer, which is named Cisk, a lager. Yes, Cisk is tasty, but it’s bitter in comparison to Mythos. I definitely prefer my Mythos.

Thwarted, we walked up Republic Street. A short way up the street, we came across a little hole in the wall café and stopped for something cool to drink. I took the opportunity to try the local Maltese beer, which is named Cisk, a lager. Yes, Cisk is tasty, but it’s bitter in comparison to Mythos. I definitely prefer my Mythos.