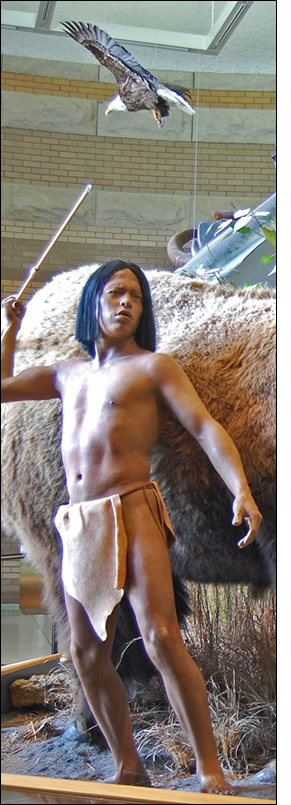

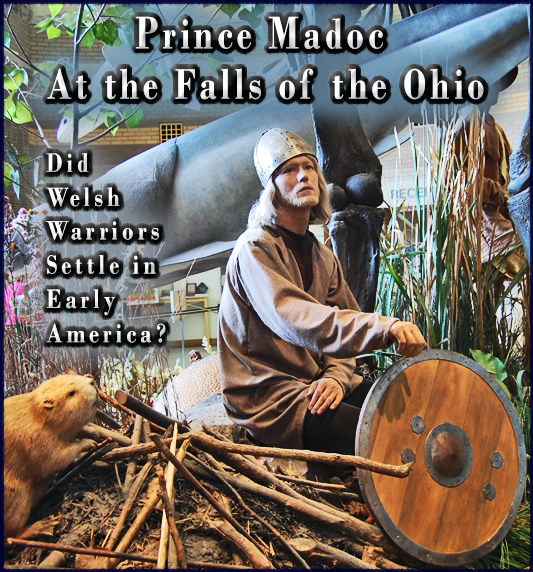

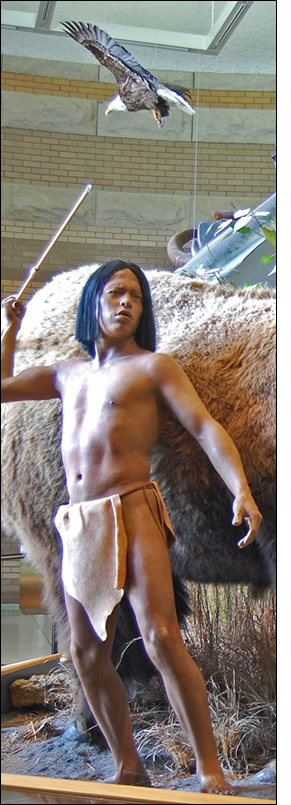

Photo by Ron Fritze on May 22, 2011

An exhibit at the Interpretative Center of the Falls of Ohio State Park in Jeffersonville, Indiana, places one of Prince Madoc's warriors into the symbolic tableau of local history.

Our Search for the Facts

Places Myth against Legend

In the Annals of Early America.

Tales of a Prince and Adventures

In Pre-Columbian North America

"When Kentucky was a part of Virginia there was a tradition widespread and generally believed that a Welsh prince by the name of Madoc planted a colony of his countrymen in America about the year 1170. This colony was believed to have been located for some time at the Falls of the Ohio, where, after it grew strong and became offensive to the more numerous aborigines, it was attacked with overwhelming numbers and nearly all members slaughtered."

— Reuben Durrett,

Traditions of the Earliest Visits of Foreigners to North America,

Filson Club Publications no. 23

(Louisville,KY: John P. Morton Company, 1908), p. 1.

By Ronald Fritze

Posted on June 14, 2011, from Athens, Alabama

I recently had an opportunity to visit the Falls of the Ohio State Park in Jeffersonville, Indiana. At this point, some of you are asking, “Falls of the Ohio?” And some of you are asking, “Where’s Jeffersonville, Indiana?” Let me start with Jeffersonville. It is across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, along with New Albany and Clarksville. As for the Falls of the Ohio, they are located right there at Louisville and Jeffersonville. You should not think of them as great towering creations like Niagara Falls. They are, or were, a series of rapids, sort of like the rapids at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River or the cataracts on the Nile.

The Ohio River has long been regarded as a very picturesque river. The name “Ohio” derives from an Iroquois word meaning “good river.” The early American settlers of the Ohio River considered it to be a good river — navigable for its entire length, from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Cairo, Illinois, except at the Falls of the Ohio, where the river experiences a 26-foot drop over the course of two and a half miles of rapids.

During parts of the year, the rapids were navigable, but at other times, boats would have to portage, hence the location of Louisville and Jeffersonville. This point in the river was a strategic bottleneck for traffic. As Americans settled the Ohio Valley, various projects to dam the river and build locks to make it navigable to larger boats were gradually completed. As a result of these improvements, most of the old rapids are permanently covered with water behind a dam.

The Now and The Then

Are on Display at a Great Park.

If you want to visit the Falls of the Ohio, you’ll find a lovely state park with a great interpretive center. To get there, just get on I-65 and take Exit 0 on the Indiana side of the river. Signs will direct you to the park. The day I visited, the weather at the Falls was nice and sunny, although there was a nasty front moving across the central states. The park is located on the river side of the levee. Its grounds are very pleasant with walkways and overlooks for viewing the Ohio River. If you ever visit there, I suggest bringing a picnic lunch if the weather is pleasant. Next to the Interpretive Center is an observation deck for the river and the remaining rapids.

The river was up the day of my visit. You could see a lot of flotsam and jetsam on the banks. The park has paths for hiking, access to fishing, and camp grounds for picnics and overnight stays. You can also take wooden stairs down to the river to look around, although signs warn you to head for high ground if you hear sirens, which signal they are opening a spillway on the dam — the water can get deep very quickly. Exciting stuff.

What they don’t want you to do is fossil hunt. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the limestone of the falls were an ancient seabed, creating a wealth of fossils of prehistoric shell fish. It is supposed to be the richest site for Devonian fossils in the world. Another interesting piece of history is that in 1803 Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began their great expedition to explore the Louisiana Territory from the Falls of the Ohio. An additional attraction is the homestead of George Rogers Clark, the Revolutionary War military leader and the older brother of William Clark. His house is quite near the park, but I did not get to visit it because the high water had flooded the grounds around the house. Not a problem. I enjoyed my visit to the Falls of the Ohio, so I will be back.

The park has a fine modern Interpretive Center. It is a sort of museum with exhibits on various topics. Some of the displays deal with the natural history of the plants and animals of the Ohio Valley. Other exhibits deal with its abundant fossils. Some cover topics related to the early scientists who studied this area. There are also presentations about the ice ages and prehistoric mammals. In fact, when you first enter the Interpretive Center you see a big display with a mammoth skeleton as the centerpiece. Other cases deal with the pre-Columbian Indians, the historic Indians, the early explorers and settlers of the Ohio Valley, and the economy and river transportation on the Ohio River during the nineteenth century — fascinating stuff and well presented.

We Arrive at the Intersection

of Myth, Legend, and Pseudo-history.

Remember, I am a guy who is interested in pseudo-history, so maybe it’s time we strayed from all this talk about “real” history into the realm of invented knowledge. According to advance notice, the Interpretive Center was supposed to have an exhibit concerning Prince Madoc and the settlement of North America by some medieval Welsh. Was there really such an exhibit? I made my way through the museum, keeping an eye open for it as I enjoyed the other exhibits. Turning a corner, I found what I was seeking: a display case titled “Myths and Legends,” containing materials related to the myth of Prince Madoc.

Keep in mind, I am calling it the myth of Madoc, not the legend of Madoc. Although myth and legend are frequently used interchangeably (which I think is what the Interpretive Center has done), the two words have precise and distinct definitions when used in a scholarly sense. Myth refers to a made-up story that has no basis in historical events. Legends are stories about past events that have a historical basis. A famous example of this use of legend is the Trojan War. It was long thought to be a myth, a made–up story with no basis in history. Then the amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schleimann did some excavating in Turkey and discovered the site of Troy. He found that the city had been sacked and burned at about the right time to be equated with Homer’s Trojan War. Most scholars agree with me about Madoc, but other people think the story is a legend that reflects actual historical events.

Where do the Falls of the Ohio come into the myth of Madoc? The Interpretive Center’s exhibit tells the story in a nutshell, but I’ll take the time here to present an expanded version of the myth.

A Civil War in Wales

Leads the Prince Westward

To an Unknown Land.

Madoc was one of the many sons of Owen Gwynedd, the ruler of northern Wales. When Owen died in 1169, a vicious civil war broke out among his sons. Not wanting to become a victim of fratricide, Madoc decided to go on a long ocean cruise with some of his followers. Sailing west, they found an unknown land and liked what they saw. So Madoc returned to Wales to organize a settlement in the new country. A second and possibly a third voyage followed. There are many suggestions for where Madoc landed. Two are specifically connected to the Falls of the Ohio.

In one version, Madoc sailed up the mouth of the Mississippi River and entered the Ohio, finally stopping at the Falls of the Ohio. The other version has the Welsh explorers land at Mobile Bay near the location of Fort Morgan. Moving inland and northward, they established a nice kingdom in northern Alabama and Georgia and in

southeastern Tennessee. Being civilized, Christian and white, the Welsh were very successful, but their success aroused the jealousy and fear of the neighboring tribes of much more primitive Native Americans. A war breaks out and the outnumbered Welsh are forced to retreat to the north.

southeastern Tennessee. Being civilized, Christian and white, the Welsh were very successful, but their success aroused the jealousy and fear of the neighboring tribes of much more primitive Native Americans. A war breaks out and the outnumbered Welsh are forced to retreat to the north.

At this point, the fleeing Welsh reach the Ohio River, where somehow the two versions of Madocian lore begin to merge. The Welsh settle around the Falls of the Ohio and create a second successful kingdom — unless they came up the Mississippi, in which case this would be their first kingdom. Unfortunately, those pesky and primitive Native Americans just can’t stand the Welsh being so successful, so war breaks out. Still outnumbered, the Welsh made a stand on Sand Island by Louisville and are defeated. The remnant retreated down the Ohio and then up the Mississippi to the Missouri River. They are harried up the river until it is finally safe to settle down, at which point they evolve into what became the tribe of the Mandans.

Show Us the Evidence.

What is the evidence for a medieval Welsh presence at the Falls of the Ohio? The search for an answer leads us into a rich realm of frontier folklore and tall tales. No reliable and authenticated archaeological evidence exists, and the voyage of Madoc left no documentary trail dating from the twelfth century for historians to study. Surviving documentary evidence only begins in the sixteenth century, and it was produced by people who were hardly objective or disinterested.

Furthermore, the sixteenth century documents do not supply any of the details included in the above narrative. In the myth of Madoc, the Native Americans seem to be primitive savages, which bespeaks the myth’s origins in a frontier America where giving the aboriginal inhabitants credit for any virtues or accomplishments was rare. If Madoc actually had visited North America after 1170, he would have encountered the complex and civilized chiefdoms of the early centuries of the Mississippian culture. In fact, the Welsh fleeing their defeat at the Falls of the Ohio would have had to pass by the great urban center at Cahokia, the biggest city to have existed in pre-Columbian North America. These people were not nasty brutes armed with bows and arrows and sporting Mohawk haircuts.

Supporters of the historicity of the medieval Welsh discovery and settlement of North America will make claims about the existence of allegedly authentic artifacts. There are claims that the remains of armored Welsh warriors have been dug up on Sand Island. In 1799, there was supposedly a discovery of the armored bodies of six Welshmen at Jeffersonville, Indiana, but the story cannot be satisfactorily confirmed and the armor is nowhere to be found.

A Welsh fortification was supposedly located on the peninsula known as the “Devil’s Backbone” where Fourteen Mile Creek flows into the Ohio River. This site is near Charlestown, Indiana. Unfortunately the building of the Big Four Railroad Bridge between 1888 and 1895 resulted in the destruction of the stone walls. Later an amusement park named Rose Island was built on the same location during the 1920s, further clouding any archaeological evidence that might have remained.

Armor and Coins, So They Claim,

Lead All the Way Back to Madoc's Men.

The exhibit in the Interpretative Center focuses on two artifacts. The first artifact is a set of medieval Persian armor. A man named John Brady discovered some Persian armor during 1898 while walking to work in Louisville. Experts from the Smithsonian Institution and the Field Museum of Chicago confirmed that it was authentic Persian armor, but they could not say how it ended up buried in at the Falls of the Ohio. Supporters of the Madoc story suggest that a medieval Welsh crusader brought it back home after he finished his time in the Holy Land. The armor later ended up traveling to America with Madoc’s people. Again, misfortune struck this artifact as it was stolen from the Brady family in 1968 and has never been recovered. Only pictures taken by the Brady family remain. The idea of a medieval Welsh crusader bringing Persian armor to America just seems somewhat tenuous to me.

The second artifact is a cache of Roman coins unearthed in 1963. A small pile of coins was uncovered during a construction project in New Albany, Indiana. The coins date from the reigns of Maximus I and Claudius II, respectively 235 and 268 AD. Madocians suggest that one of the Welsh warriors was carrying these coins and lost them during the great struggle with the Native Americans of the Ohio valley. While it is possible than a Welshman was carrying 900-year-old coins with him to America, it is more probable that some hapless coin collector lost the treasures much later, and that in1963 they were found. That is what the Interpretive Center’s exhibit suggests, and rightly so.

Now if you are interested in a more detailed recounting of these sorts of evidence from a Madocian point of view, see Dana Olson, The Legend of Prince Madoc, Discoverer of America in 1170 A.D. and the History of the Welsh Colonists, also Known as the White Indians or the Moon-Eyed People (Jeffersonville, IN: Olson Enterprises, 1987).

You have probably noticed that substantial artifacts left by medieval Welsh settlers have an unbroken record of being found and then lost again. These circumstances do not provide a solid foundation for proving that Prince Madoc ever visited America and established a colony. At the same time, I applaud the staff of the Falls of the Ohio Park for including a Madoc exhibit in their collection. It is an evenhanded presentation, which means it will please neither convinced Madocians nor fierce skeptics. That is always the sign of a good compromise.

Don't Be Embarrassed.

Have Some Fun with It All.

Myths such as the story of Madoc abound. They form a part of the history and folklore of a locality and even a nation. As such they need to be studied and talked about. Park services have tended to try and ignore things like the Madoc myth. These myths are viewed as an embarrassment. That is certainly the case of the museum at Fort Morgan in Mobile Bay. They really need to have an exhibit that says up front that many people have believed and continue to believe that Madoc and his followers landed here at Mobile Bay, but while it is a fun story, there is no serious evidence that it is a true story.

Apart from the Madoc exhibit, the myth of the medieval Welsh gets a prominent display at one other place in the Interpretive Center. Remember the big display in the entrance, the one featuring the mammoth? In addition to the mammoth, there is a Devonian era shark, a Paleo-Indian with a spear and atlatl, a buffalo, some beaver building a lodge — and, kneeling at the side, a bearded blonde man in medieval clothing and a helmet. He is one of Madoc’s warriors. I like it.

My recommendation for anyone passing north or south on I-65 through Louisville is to stop and enjoy the Falls of the Ohio. It is a beautiful park and a place full of natural history and human history.

|

southeastern Tennessee. Being civilized, Christian and white, the Welsh were very successful, but their success aroused the jealousy and fear of the neighboring tribes of much more primitive Native Americans. A war breaks out and the outnumbered Welsh are forced to retreat to the north.

southeastern Tennessee. Being civilized, Christian and white, the Welsh were very successful, but their success aroused the jealousy and fear of the neighboring tribes of much more primitive Native Americans. A war breaks out and the outnumbered Welsh are forced to retreat to the north.