Lost —

Early Modern

Style

The Roanoke Colony

and Early Settlements

in North America.

By Ronald Fritze

Posted on November 17, 2008, from Athens, Alabama

One of the chiefe trees or postes at the right side of the entrance

had the barke taken off, and 5. foote from the ground in fayre Capitall letters was graven CROATOAN without crosse or signe of distresse.

John White, Narrative of the 1590 Voyage.

For anyone interested in history today, it is clear that England had a tremendous influence on the settlement and development of the North American continent. Both the United States and Canada are former colonies of England. Although they have significant Spanish and French speaking minorities and are nations of immigrants, the predominant language, institutions, and culture of both countries are English. This outcome, however, would not have seemed all that likely to someone living in the sixteenth century or even the first three decades of the seventeenth century.

England, or rather John Cabot, officially discovered North America in 1497, although ships from Bristol might have preceded the sea captain and explorer. Like Columbus, Cabot thought he had reached Asia. When he again sailed west in 1498, Cabot was never seen again.

Henry VII and Henry VIII never seriously tried to follow up his discovery, but that is not surprising since Cabot had landed in the area of modern Newfoundland and Labrador. The explorer thought he had reached Marco Polo’s Anian (modern Siberia). But one or the other, the result was the same: Cabot’s discovery was a cold and desolate land.

Although the fishing was bountiful, Newfoundland was not inviting for permanent settlement. It lacked portable wealth like gold or silver and possessed no verdant farmland. By European standards its inhabitants were primitives. No wonder the Tudor monarchs quickly lost interest in a land that offered so little to their ambitions.

The same fate almost befell Columbus’s settlements on tropical Hispaniola and Cuba after it was realized that large supplies of spices and gold would not materialize.

At this stage in the age of discovery, European explorers were seeking a way around or through the Americas. They had little interest in setting up colonies there.

Gold! Silver! Plunder!

Things changed after Hernan Cortes discovered the wealthy and highly civilized Aztec Empire in 1519. Francisco Pizarro followed up by revealing the existence of the fantastically rich Inca Empire in

1530. The conquest of these two empires provided Spain with plunder, but those early riches were soon surpassed by the development of silver and gold mines.

1530. The conquest of these two empires provided Spain with plunder, but those early riches were soon surpassed by the development of silver and gold mines.

Great treasure began to flow into Spain, making the king of Spain the richest ruler in Europe. Other ambitious royals and ambitious members of their courts began to wonder if other empires of gold and silver might be found across the seas.

The Spanish thought so, sending expedition after expedition across the seas in search of treasure.

Other Europeans, including the English, wanted their share of this cornucopia of precious metals. Finding gold and silver on their own would have been nice, but failing in that endeavor wasn’t

the end of the matter. Stealing from the Spanish seemed a reasonable substitute for discovery. There were plenty of willing pirates, too.

the end of the matter. Stealing from the Spanish seemed a reasonable substitute for discovery. There were plenty of willing pirates, too.

French corsairs flocked to the Caribbean with the English and Dutch following later. Suddenly, North America became of interest again. English expeditions sailed to establish settlements, or at the least to establish naval bases from which to raid Spanish treasure ships.

Early Failure

Dampens Enthusiasm.

The first of these expeditions took place in 1536 when Richard Hore sailed two ships to the Newfoundland region. The participants in this poorly prepared venture suffered greatly while managing to discover nothing of value to the crown. Hore’s failed voyage cooled English interest in North America for several more decades. Englishmen made trading voyages to the Caribbean basin and South America, but their talk of colonies in North America subsided.

What did fascinate explorers was the possibility of finding a Northwest Passage.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (1539?-1583) was attracted to the quest for a Northwest Passage to Asia, but he also began to see the benefits of establishing English colonies in North America. These settlements, he reasoned, would engage in trade and commerce, and thus provide the destitute and rootless among the English with a place to live and work. Gilbert wrote a tract making that argument in 1576. Two years later Queen Elizabeth granted him a patent that licensed him to explore and establish settlements in North America.

Gilbert quickly organized an expedition of ten ships, but stormy weather in the Atlantic Ocean forced all of them to turn back

before they could reach North America. Various problems prevented him from sailing again until 1583, this time with a fleet of five ships departing from Plymouth. Gilbert reached Newfoundland in July. From there he sailed to St. John’s, where on 5 August he took possession of the region for England, despite the fact that fishing vessels of Spain, Portugal, and France had been visiting the islands for some years.

before they could reach North America. Various problems prevented him from sailing again until 1583, this time with a fleet of five ships departing from Plymouth. Gilbert reached Newfoundland in July. From there he sailed to St. John’s, where on 5 August he took possession of the region for England, despite the fact that fishing vessels of Spain, Portugal, and France had been visiting the islands for some years.

After sailing south to Nova Scotia, Gilbert decided at the end of August to return to England. It was a fateful decision. His over-burdened, too-small vessel ran into high seas and bad weather. On 9 September a companion vessel lost sight of the lights on Gilbert’s ship. It was assumed that his ship had foundered in the great waves. Gilbert was never seen again — and the mantle of pursuing North American settlements passed to his half-brother, Sir Walter Ralegh (1554?-1618).

Ralegh Spelled Any Ole Way

Is Still the Great Explorer.

Ralegh — whose name was spelled Rawley, Rawleygh, Ralle, and Raulie, among several dozen other variants, but was never spelled Raleigh in his lifetime — gained Gilbert’s patent to explore and settle North America in 1584. That year he sent Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to explore under his banner. They reached the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

The next year, Ralegh dispatched a fleet under the command of

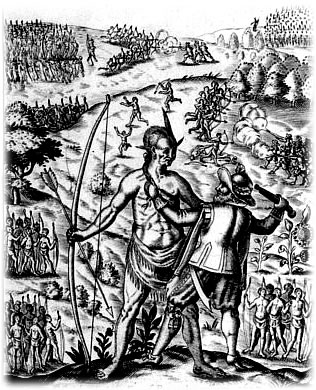

Sir Richard Grenville with orders to establish a North American settlement along the Outer Banks. A pugnacious gentleman, Grenville would eventually go down fighting the Spanish against overwhelming odds in 1591. For Ralegh he built a fort on Roanoke Island, which had the virtue of being located in the waters on the inside of the Outer Banks. The location provided protection from both storms and the prying eyes of Spanish patrols seeking to eliminate any interlopers in their American domain. It was a very real danger, too, as the Spanish had ruthlessly massacred the French settlement of Jean Ribault in what is now South Carolina during 1565.

Sir Richard Grenville with orders to establish a North American settlement along the Outer Banks. A pugnacious gentleman, Grenville would eventually go down fighting the Spanish against overwhelming odds in 1591. For Ralegh he built a fort on Roanoke Island, which had the virtue of being located in the waters on the inside of the Outer Banks. The location provided protection from both storms and the prying eyes of Spanish patrols seeking to eliminate any interlopers in their American domain. It was a very real danger, too, as the Spanish had ruthlessly massacred the French settlement of Jean Ribault in what is now South Carolina during 1565.

Grenville returned to England, leaving Ralph Lane in command of a garrison of 100 men. Lane’s explorations uncovered some intriguing but ultimately false information about potential gold and copper mines and useable ship passages to Asia. Meanwhile, conditions at the Roanoke fort deteriorated rapidly. Food became scarce and the native tribes became increasingly hostile. When the fleet of Sir Francis Drake unexpectedly stopped at the settlement, Lane and the surviving garrison asked to be taken back to England. Drake obliged.

Soon thereafter, Grenville returned with supplies and more settlers. Disgusted that the colony had been abandoned, he sailed away, leaving behind fifteen men with orders to hold the position. The fifteen were killed by hostile Indians.

White's Expedition

Leads to a Profound Mystery.

Ralegh organized another expedition in 1587 under the leadership of John White, the artist and a survivor of Ralph Lane’s settlement. The plan was to place the new settlers in the Chesapeake Bay, but when White’s ships reached Roanoke, the expedition’s pilot, Simon Fernandes, refused to sail further north. The settlers were forced to stay at Roanoke.

White proved a poor leader. Soon the settlement’s supplies were deemed inadequate to sustain life, so White decided in late summer to return to England to get more supplies and additional settlers. He left behind 114 people, including his own family and the newly born Virginia Dare, the first English child born in North America.

Unfortunately for White and the Roanoke settlers, England’s impending war with Spain flared up into a full-scale conflict, complicating the prospect of sea passages. White made an unsuccessful attempt to return to Roanoke, but the threat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 diverted everyone’s attention to the defense of England.

White finally returned to Roanoke in 1590, only to find the settlement deserted. All he found was the word CROATOAN carved carefully into a tree. The 114 settlers from 1587 were never seen again. Their fate became one of the great mysteries of history.

War with Spain prevented England from establishing any new settlements for years. Finally in 1606, the new king James I granted the London Company and the Plymouth Company the right to set up colonies in North America.

An expedition of settlement sailed from London on 22 December 1606. Going by way of the West Indies, the fleet reached Chesapeake Bay on 26 April 1607. After exploring the James River for about two weeks, the expedition leadership decided to place the new settlement at Jamestown Island.

Here Comes Pocahantas,

But Be Sure to Hide Your Eyes.

Many adventures followed. The local Indians proved even

more hostile than the Indians living on or near Roanoke. The greatest chief of the region, Powatan, clearly viewed the English settlers as a potential threat. Powatan saw the interlopers as incompetent spongers who were incapable of producing enough food to feed themselves.

more hostile than the Indians living on or near Roanoke. The greatest chief of the region, Powatan, clearly viewed the English settlers as a potential threat. Powatan saw the interlopers as incompetent spongers who were incapable of producing enough food to feed themselves.

His daughter felt quite differently about the English. She would famously save Captain John Smith. Later she would marry John Rolfe and become a celebrity in England. English settlers, at least the males, were quite fond of Pocahantas — and no wonder. At age fourteen, stark naked, she performed cartwheels around the settlement. She also led a couple of processions of scantily clothed Indian maidens into the settlement. More importantly for history, she continually advocated on behalf of the colonists to her skeptical and antagonistic father. On several occasions she even provided the colonists with warnings of potential attacks.

Despite famine, disease, and the hostility of Powatan’s warriors, Jamestown survived to become the first permanent English colony in North America. Thus took root an experiment in colonization that would eventually mature into the United States of America. Still, when compared to the cities of Spanish America, this struggling English colony, along with the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies further north, were small and rather unimpressive enterprises in their early years.

The seeds of future greatness had been sown. But maturation would be a long, tedious, and sometimes tragic process.

The Lost Ones

Assume Many Guises.

And what about the lost colony of Roanoke? Many reports of the Lost Colonists came into the hands of the English,

but most proved to be unreliable or false. Efforts to search for the Lost Colonists failed to find them. The best evidence indicates the colonists abandoned Roanoke Island for the area around Cape Henry at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, although a small party of men went to Croatoan Island to the south to watch for rescue ships from England. Both groups mixed with the neighboring Indians.

but most proved to be unreliable or false. Efforts to search for the Lost Colonists failed to find them. The best evidence indicates the colonists abandoned Roanoke Island for the area around Cape Henry at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, although a small party of men went to Croatoan Island to the south to watch for rescue ships from England. Both groups mixed with the neighboring Indians.

When the Jamestown settlers arrived, the nervous Powatan became worried. Prophecies from the Indian religious leaders claimed that the third settlement of strangers would survive and that Powatan’s empire would be destroyed. Remember, Lane and White’s settlements were the first and second colonies. Powatan decided to mute the prophetic voice by wiping out the Roanoke survivors. His warriors managed to kill most of them, but a few escaped into the woods and were absorbed into more sympathetic tribes resentful of Powatan’s domination. The men on Croatoan Island were also eventually merged into the local Indian population.

The Lost Colonists became a rich source of pseudo history, either fueling tales of White Indians on the frontier, or inspiring myths such as that of Prince Madoc and his medieval Welsh colonies in North America.

Studies of DNA are underway today to determine if there is any genetic evidence of the Lost Colonists. As is frequently the case, the scientific results have so far been inconclusive and subject to various interpretations. Still, the romance of the Lost Colonists of Roanoke persists as one of history’s more intriguing mysteries. It remains an enduring symbol of England’s faltering early efforts to colonize North America.

Seagull: Come, boys; Virginia longs till we share the rest of her maidenhead.

Spendall: Why, is she inhabited already with any English?

Seagull: A whole country of English is there, man, bred of those that were left there in ‘79. They have married with the Indians and make ‘hem bring forth as beautiful faces as any we have in England; and therefore the Indians are so in love with ‘hem that all the treasure they have they lay at their feet.

— George Chapman, Ben Jonson, and John Marston, Eastward Ho! (1605)

To read Dr. Fritze's previous Tudor-Stuart essay, England's Gunpowder Plot of 1605: Guy Fawkes Day Recalls a Bye-Gone Age of Religious Terrorism,, click the reading glasses above.

|