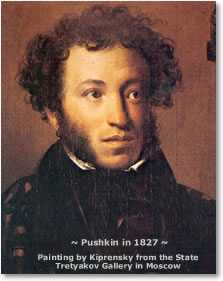

Alexander

Sergeyevich

Pushkin

1799-1837

LIVE BY THE PEN,

DIE BY THE SWORD.

Born:

May 28th, 1799,

Moscow.

Died:

January 29, 1837

St. Petersburg.

The Greatest Poet.

By Dr. Todd Alden Marshall

September 1, 2003

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (1799 - 1837) is without a doubt the most beloved writer of Russia. He is Russia's golden icon of both poetry and prose. After reading a piece of writing by Pushkin, you feel that you have connected with the Russian soul. Pushkin made the Russian language come alive and speak like no one before him.

Russian children learn to recite certain poems by Pushkin at a very early age. By the time they are adults they will have been exposed to many of his writings. Also, Pushkin's works often are the basis for many Russian cartoons, children's books, and songs.

The Mysteries of Translation.

My first encounter with the works of Pushkin was at the Monterey Institute where I was studying Russian. One of my teachers introduced me to the poem 'I loved you' (1829) and I instantly fell in love with the melodic verses of Pushkin. I have included two translations of this poem because I can't decide which one I like best. I find the first translation (A) to be more literally on the mark, and from a professional point of view it is quite good. However, it lacks the emotional sense of loss that I feel comes out more clearly in the second translation (B).

Translation A

I loved you: and, it may be, from my soul

The former love has never gone away,

But let it not recall to you my dole;

I wish not sadden you in any way.

I loved you silently, without hope, fully,

In diffidence, in jealousy, in pain;

I loved you so tenderly and truly,

As let you else be loved by any man.

© Copyright, 1996

Translated by Yevgeny Bonver, August 1995,

Edited by Dmitry Karshtedt, July 1996.

Translation B

I loved you; and I probably still do,

And for awhile the feeling may remain —

But let my love no longer trouble you:

I do not wish to cause you any pain.

I loved you; and the hopelessness I knew

The jealousy, the shyness-though in vain —

Made up a love so tender and so true

As may God grant you to be loved again.

© Copyright, 1996

Translated by Genia Gurarie

Pushkin's

Pushkin's

contribution

to Russian literature is often compared to Shakespeare's contribution to English literature. Shakespeare wrote his works at a time when English was still in a youthful state of transformation, malleable and fluid. He capitalized on this fact. In like manner Pushkin used the Russian language like no one else had before him. He played with the language, leaning often to the archaic forms of Russian (based on the language of the Church, referred to as "Old Church Slovanic"), and then forging full speed into new territory, breaking the norms by using the spoken vernacular, including a lexicon filled with words from French, German, and Western European languages.

Like Shakespeare and English, Pushkin had a profound understanding of the Russian language and delighted in making each word come alive. Pushkin knew how to use the language to his own advantage. The nuance of his words is sometimes hidden in clandestine verse. Then, unexpectedly, it bursts into the open with original directness.

Pushkin's Early Years.

Aleksandr Pushkin was born in Moscow. His family was educated, but poor. His father was a descendant of an ancient noble family, and his mother was a descendant of Hannibal, a black Abyssinian. Gannibal was a serf who served under Peter the Great. This made Pushkin the great-great-grandson of Gannibal. Peter adopted him as his godchild with the goal of proving to his Russian court that any man, despite his color or race, could be transformed from slave to 'man' if given the right kind of upbringing and education. His benevolence allowed Gannibal to rise in status, to a place no African had ever before achieved in European society. Russia proved to be well advanced in this matter.

Pushkin was proud of his ancestral heritage. His The Blackamoor of Peter the Great (1828) is rich in biographical data of the poet's black great-grandfather, Ibrahim Petrovitch Gannibal. In the excerpt below one can sense the love that Peter had for Gannibal:

"Ha! Ibrahim?" he exclaimed, getting up from the bench. "Welcome, godson."

Ibrahim, recognizing Peter, was about to rush up to him with joy, but stopped respectfully. The Emperor came up to him, embraced him, and kissed him on the head.

"I was informed you'd soon be arriving," said Peter, "and I came out to meet you. I've been here waiting for you since yesterday." Ibrahim could not find words to express his gratitude. "Let your carriage follow behind us," continued the Emperor, "while you sit with me. Let's set out for home."

Pushkin's Education.

Pushkin's grandmother taught him French, usually by telling him stories in the language. This was not uncommon since nobles of the court at this time were mostly fluent in French. Pushkin learned Russian from the household serfs and his nanny. He started writing poems from an early age. His first published poem was written when he was only fourteen-years-old. His first major work was Ruslan and Ludmila (1820), which he wrote while a student at the Imperial Lyceum from 1811 to 1817.

At the end of his studies at the Lyceum he took a post at the foreign office at St. Petersburg. There he would make friends with members of a radical movement who participated later in the Decembrist uprising in 1825. Puskin's association with this organization and other liberal groups would soon cost him his freedom.

A Verse Novel

and a Historical Tragedy.

For his open views and run-ins with the authorities, Pushkin spent a significant part of his life in exile in different parts of Russia. However, this did not stop him from writing. In 1823 he started his major masterpiece, the novel in verse Eugene Onegin, which appeared in 1833. His great historical tragedy, Boris Godunov, was published in 1831. This work was based on the career of Boris Fyodorovich Godunov, the czar of Russia from 1598 to 1605.

One of the pinnacles of Pushkin's prose was The Queen of Spades. "Its three main characters — all negative — are surrounded by an intricate system of images, signifying winter and night, doom and madness, chaos and destruction," a critic wrote. "In this story Pushkin succeeds in drawing the kind of complex characters that eluded him in the early fragments."

Pushkin's troubles with the authorities continued. In 1824 he was banished to his family estate of Mikhailovskoe, but after a while Nicholas I allowed Pushkin to return to the capital, if he abandoned his openly revolutionary sentiments.

The Fatal Wound of Love.

In 1829 he fell in love with 16-year-old Natalya Nikolayevna Goncharova. Two years later he married her. Even this arrangement would prove to be a fatal mistake. In time she would spend all of his money and leave him with huge debts, not to mention the fact that she was having an affair with the Baron George d'Anthes. This action led Pushkin to challenge the baron to a duel. The great writer received a fatal wound and died on February 10, 1837.

"The Land of Moscow..."

From "The Reminiscences at Tsarskoe Selo"

The land of Moscow — the land that is my native,

Where in the dawn of my best years,

I spared the hours of carelessness, attractive,

Free of unhappiness and fears.

And you had seen the foes of my great nation,

And you were burned and covered with blood!

And I did not give up my life in immolation,

My wrathful spirit just was wild!...

Where is the Moscow of hundred golden domes,

The dear beauty of the native land?

Where yore was the real peer to Rome,

The ruins, miserable, lied.

Oh, how, Moscow, for us, your sight, is awful!

The buildings of landlords and kings are fully swept,

All perished in a flame. The towers are mournful,

The villas of the rich are felled.

And where the luxury was thriving,

In shady parks and gardens, in the past,

Where myrtle was fragrant, limes were shining,

There now are just coals, ash, and dust.

At charming summer nights, when silent darkness roves,

The noisy gaiety would not appear there,

The lights are vanished over lakes and groves,

All dead and silent. All unfair.

Be calm, o, Russia's banner's holder,

Look at the stranger's quickly coming end,

On their proud necks and void of labor shoulders,

The Lord's vindictive arm is laid.

Behold: they promptly run, without look at road,

In Russian snows their blood like river's flood,

They run in dark of night, felled by famine and cold,

And swords of Russians, from behind.

Translated by Yevgeny Bonver, December, 1999

Edited by Dmitry Karshtedt, February 2000

*This is the next step toward THE One World Language.

Step Eleven: *Your metaphor on a cupcake!

Planet Russkij is ruled by Dr. Todd Alden Marshall, professor of Russian and Slavic Linguistics at the University of Central Arkansas. An independent entity in the CornDancer consortium of planets, Planet Russkij is dedicated to the study and exploration of the Russian language, culture, and society. CornDancer is a developmental website for the mind and spirit maintained by webmistress Freddie A. Bowles of the Planet Earth. Submissions are invited.

|